A sad stop on my writing journey

A sad stop on my writing journey

It may sound like a cliche, but it’s true: writing is a journey. This journey takes you to many happy, satisfying places, such as those I’ve experienced recently — the release of a new book with the prospect of launch parties, giving one the chance to meet old friends and make new ones. And there’s the general buzz, the renewed energy you get from knowing that you’re an author who now has two books telling true stories sought by readers under your belt.

Writing also can take you to sad places.

That thought arose this week when I belatedly learned of the death of Craig Swartz. I found out that Craig, a Missoula man who worked as a truck driver hauling building materials for a company with offices in Missoula and Bozeman, died from heart diseases last January at his home in Missoula. I imagine he had a fatal heart attack — I was told after his death that he recovered from a heart attack in 2016 — but I’m not sure.

Craig was just 59, one of his older brothers, Leonard, also a Missoula resident, told me during a phone conversation on Monday. To someone — me — who will turn 68 in less than two weeks, that’s far too young to die. Heart disease runs in my family, too — which American family is free of it nowadays? My father underwent successful double-bypass heart surgery when he was 55, took good care of his heart and died of unrelated cancer 30 years later. His father, a grandfather I barely knew, died of a heart attack at 55. Still, a fatal heart attack shouldn’t happen to someone just easing into middle age as Craig was.

Craig Swartz joined my wife and me for lunch in Missoula last September. We dined at the Montana Club, one of the favorite eateries for my father, the late William "Bill" Gaub, a World Wor II veteran[/caption]

Although he was a casual friend, I’m writing about Craig because he represented a direct tie to an important period and an important person in my new book.

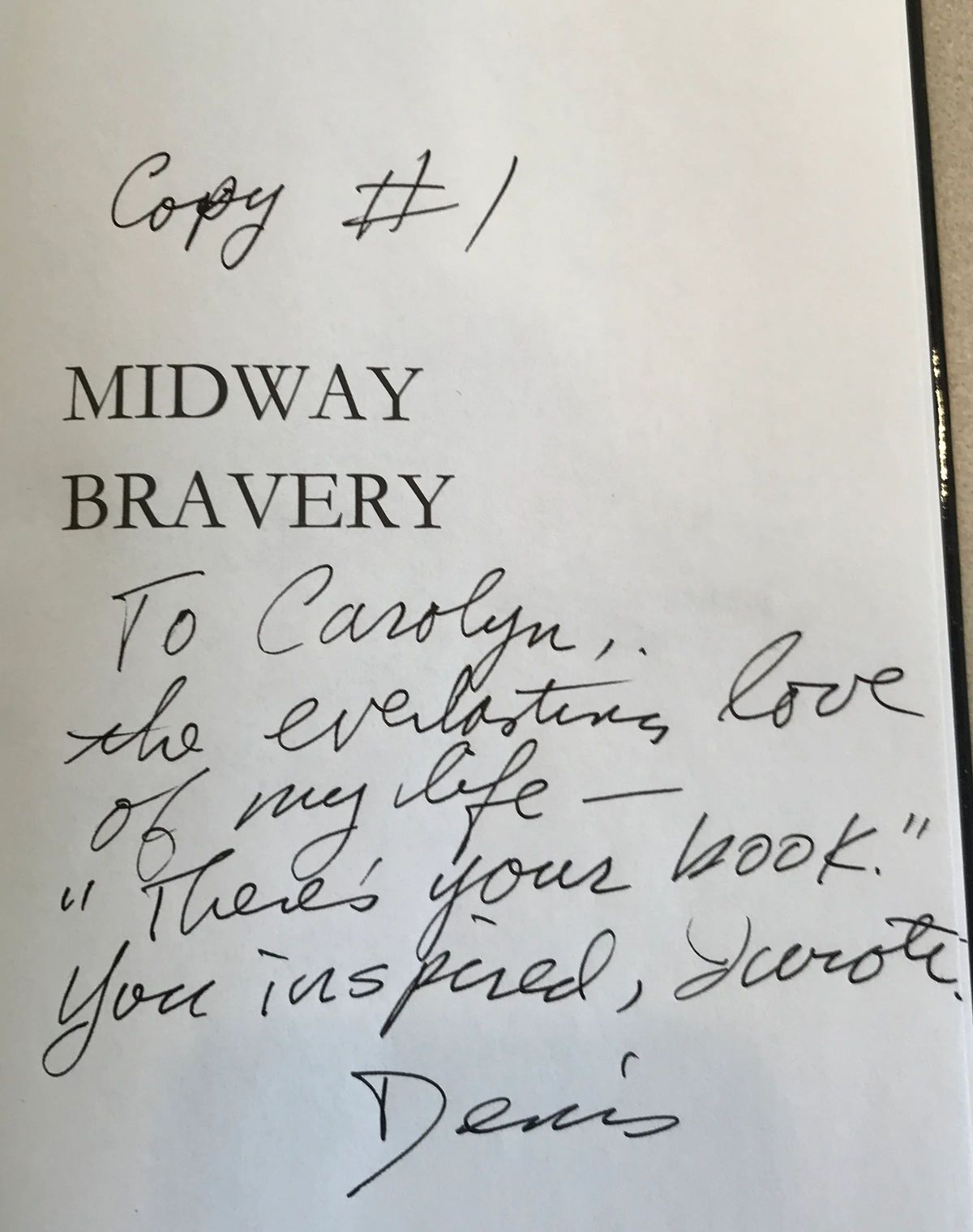

In fact, if I hadn’t met Craig by chance two summers ago, much of the rich detail found in Chapters 2 and 3 of “Midway Bravery” would not have not found its way into the book. Here’s a summary of that story within the bigger story of the life of famed World War II pilot Jim Muri.

Craig’s uncle, a man he never met, was Henry “Hank” Swartz. Hank was Jim’s best friend in high school in Miles City, and they graduated together from Custer County High School in May 1936. (Not quite 30 years later, I enrolled in CCHS and was a student there until the fall of 1967 when my family moved to Billings, Montana, where I graduated from high school.) Jim and Hank bonded through their shared love of flying. The story I’ve heard is that Hank’s parents found enough money during the depths of the Great Depression to pay for their son to take flying lessons at the Miles City airport.

It wasn’t much, but Hank benefited from having parents somehow able to afford flying lessons for their son, which wasn’t available to Jim. Second-oldest of nine children who grew up on a combined farm and ranch in rural Rosebud County, immediately west of Custer County, Jim experienced flight in vicarious fashion during his formative years. First, he gazed upwards at early Northwest Airlines flights making their way up the Yellowstone River Valley as they traveled Northwest’s Twin Cities-to-Seattle route. That gave Jim the flight bug.

Then when Hank took flying lessons, Jim went to the Miles City airport and watched his buddy gain proficiency at the controls of a small plane. Sometimes Jim had to get from his home place in the Rosebud County hamlet of Carterville to Miles City to see Hank in action. The Milwaukee Road provided an inexpensive, convenient way to travel the short distance. Jim paid a 50-cent fare and rode the train to Eastern Montana’s major town.

The two 18-year-olds, Jim and Hank, signed up for the Army after graduation in 1936. Hank enlisted earlier because his birthday came before Jim’s.

Both men set their sights on becoming pilots in the Army Air Corps, the predecessor of first the Army Air Force (AAF) that helped the Allies rule the skies in World War II and then the modern Air Force. First, though, Jim and Hank had to go through basic Army training. They got that in the same place: Chanute Field in downtown Illinois.

After that, their training paths diverged. Jim entered flight school in Glendale, California. Stationed at March Field in Riverside, California, he studied aviation subjects at Riverside Junior College and met Alice Moyer, a Riverside native who became his wife of almost 60 years.

Jim continued towards becoming a military pilot when he was assigned to the “West Point of the Air,” Randolph Field in Texas near San Antonio. After he graduated from Randolph, he trained at nearby Kelly Field. Then he was off to Langley Field near Washington, D.C., where he was introduced to the B-26, the high-performance medium bomber that would bring him fame.

Records of Hank’s progression to AAF pilot status are less complete. After Chanute, he went to Hamilton Field, a base in Novato in Northern California. He studied at Marin Junior College, worked for Douglas Aircraft Co., got an associate of arts degree from UCLA and graduated from Hancock College of Aeronautics in May 1941 as one of 56 Flying Cadets.

During his time in Northern California in 1941, Hank met a woman from Sacramento, Edna Peterson, and they married. By November that year, Hank and Edna knew they would be separated — he had received orders to go to the Philippines. This was just before Japan’s December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor.

Jim and Alice didn’t meet Edna before Hank was sent overseas, but the two Miles City pals and Jim’s Riverside fiancé — they married on December 25, 1941 — socialized and became close friends in the months before World War II became part of American consciousness. Hank’s affection for Alice comes through in how he greeted her in a letter mailed from San Francisco and a postcard sent from the Philippines that reached Alice in short order in November 1941. In the former, Hank addressed Alice as “My Dear Little Alice Blue Gown,” and in the latter, he wrote to “My Dear Little Blue Eyes.”

(To be continued)